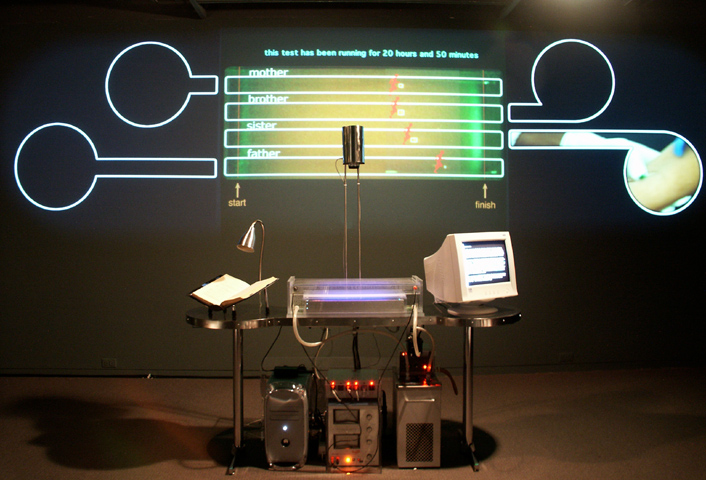

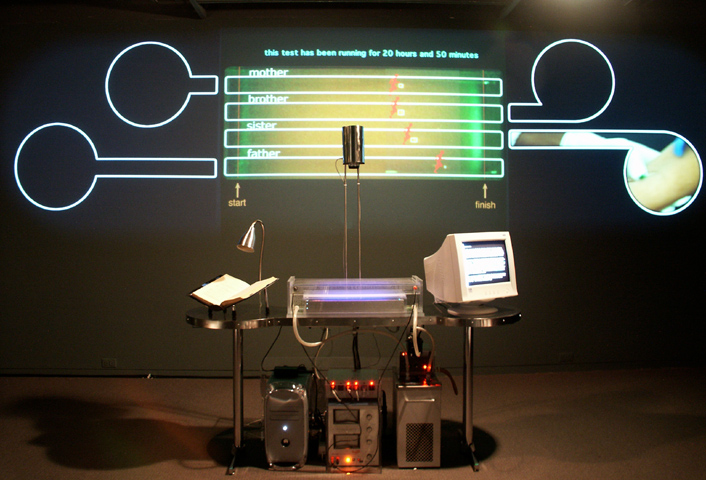

R.V.I.D. Installation View, Henry Art Gallery, Seattle, WA. April, 2002

THE RELATIVE VELOCITY INSCRIPTION DEVICE by Paul Vanouse, 2002 |

Vanouse projects |

| The Relative Velocity Inscription Device (RVID) is a live scientific experiment using the DNA of a multi-racial family of Jamaican descent. The experiment takes the form of an interactive, multi-media installation consisting of a computer-regulated separation gel (described below) through which four family members' DNA samples slowly travel. Viewer interactions with an early eugenic publication within the installation allows access to historical precursors of this "race," while a touch-screen display details the results of this particular experiment. The project merges contemporary DNA separation technologies with early 20th Century research in human genetics, particularly Eugenics. |

R.V.I.D. Installation View, Henry Art Gallery, Seattle, WA. April, 2002 |

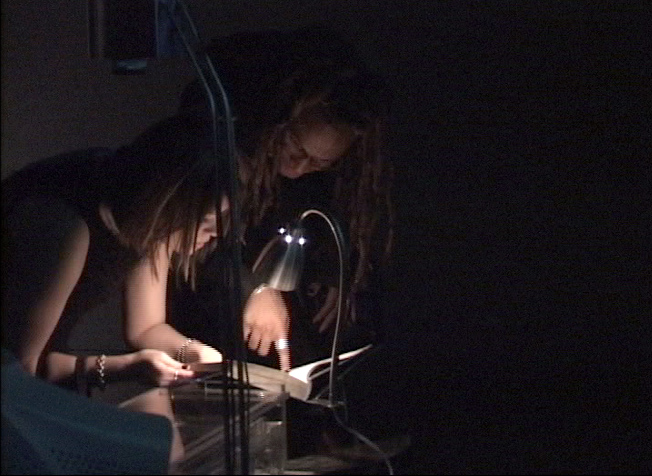

Gallery visitors examining Race Crossing in Jamaica. |

The most monumental life science project ever undertaken, The Human Genome Project, which has the goal of mapping every gene in human DNA, is nearing completion. It is important to reflect that today as in the early 20th Century, science is deeply embedded in the prevailing cultural value-system of its time. In 1929, Charles B. Davenport published Race Crossing in Jamaica. The three-year research project examined the "problem of race crossing" during the period when the new science of human genetics was strongly biologically deterministic and informed by racial separatist doctrines. The island of Jamaica was chosen for its isolated pockets of "pure-blooded negro, mulatto and White" of similar economic class. |

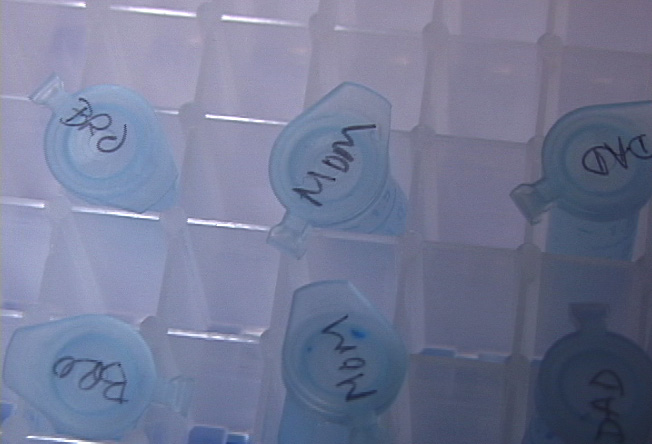

| In 1960, my ("brown") mother emigrated to the US from Jamaica, and met my ("white") father. "Why is my skin color lighter than my sister's?" Recent studies posit that there are several genes responsible for such variance. The installation utilizes DNA samples extracted from the blood of Mother, Father, Sister and Brother (myself). The samples literally race against each other in a genetic separation gel, the winner of each race changes depending upon the particular region of the DNA from which the samples were obtained. My intention is not to actually 'map' the genetic differences, but rather: a. to question the veracity of this or other scientific spectacles; and b. to create a tension in regard to each viewer's relationship to this "genetic horse-race," in terms of their own sense of racial identity. |

Genetic samples prior to loading into installation. |

|

Close up of computer projection showing a live video image of the electrophoresis gel with graphical overlays. The four bright orange dots are individual DNA samples from the four family members, which are glowing because of the UV light irradiation below the gel. |

Theorists, such as Paul Gilroy, have identified our current era as "post-biological" in part because contemporary science has focused upon molecular/computational (i.e. genomic) ways of identifying human differences rather than the anthropomorphic, epidermal and cellular traits used in the past. Since within any race there are more genetic (DNA) differences than between races, there is no genetic (DNA) basis for existing race categorizations. Optimists believe that such findings will put an end to the concept of race and thus racism. Pessimists note that science has always been used to maintain existing hierarchies and thus will be manipulated for new varieties of discrimination. RVID operates in this tense space between critical and utopian appraisals of contemporary genomics and the politics of race. It transfers the discussion of difference from the physical bodies of its subjects to their DNA, and ironically re-anthropomorphizes their DNA by inscribing value to its movements (through the gelatin) as if each sample were running a foot race to determine genetic fitness. Theorist Bill Egginton has succinctly described the RVID project as "a race about race in which the body has been erased." |

| An amplified DNA fragment from each family member is placed in each one of four channels of a custom (much enlarged) sequencing tray containing standard sequencing gel. This tray is approximately 3 feet in total length by 8 inches wide. The tray has an electrical current applied to it that causes each family member's DNA to move through the gel at a unique rate. Each race can be tailored to run for two to three days. The samples glow when bathed with Ultra-Violet light and a camera above the gel tray relays the relative positions of the four samples to a computer. The computer keeps track of who (whose DNA) wins each race. A large computer projection behind the gel tray informs the viewers of the relative position of each sample. Additionally, viewers can page through a first edition of the 1929 Davenport text to contextualize the RVID experiment and use a touch-screen monitor to access the results of previous races. The final components of the work are DVD projections showing the participants (family members), and the processes used to extract their DNA. The overall aesthetic of the work is reminiscent of bio-medical apparatus and science-museum display, made more dream-like through the UV-light illumination, and a low, humming, ambient soundtrack created live by amplifying sounds produced by the electronic, scientific equipment. |

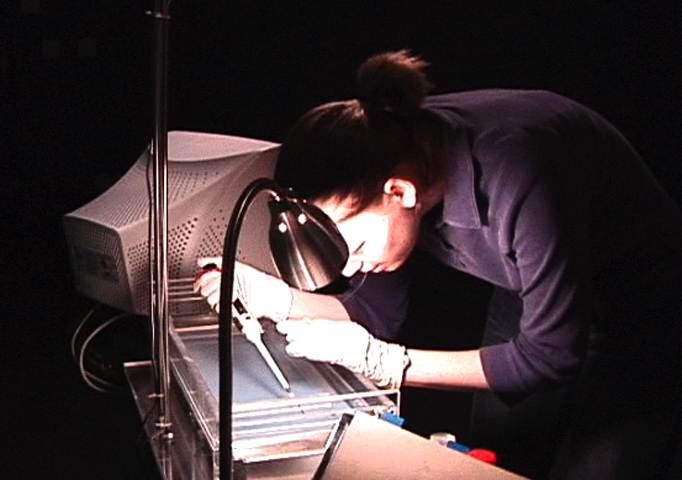

Inserting DNA. Every two to three days new DNA is inserted into the electrophoresis gel by gallery staff assistant. The insertion procedure takes about 5 minutes. |

Supported by:

New York State Council on the Arts

Henry Art Gallery, Seattle, WA.

VIDA 5.0, Art & Artificial Life International Competition, 2nd Prize.

Scientific Consultants:

Dr. Mary-Claire King, Departments of

Medicine and Genetics,

University of Washington.

Dr. Kelly Owens, Department of Genome

Sciences, University

of Washington.

Dr. Robert Ferrell, Department of Human

Genetics, University

of Pittsburgh.

Dr. Amos Dare, University at Buffalo

Dr. Maria Marchetti, Roswell Park Institute

Greg Fox, Owl Scientific

Additional Contributors,

Participants and Consultants:

Dr. Donald Vanouse, SUNY at Oswego

Chris Coleman, University at Buffalo

Caroline Koebel, University at Buffalo

Clare Bunce, Archives, Cold Spring Harbor

Laboratory

Gary Nottingham, University at Buffalo