Utter

Paul Vanouse

2024 In progress

Utter is a multi-sensory artwork based on concept of ‘utterance,’ conceived amid the COVID pandemic, in which the act of speaking is linked to viral transmission. Our utterances are semio-material, both linguistic and material, and connect us together in complex ways not just through language, but also through shared micro-materials and aromatic compounds.

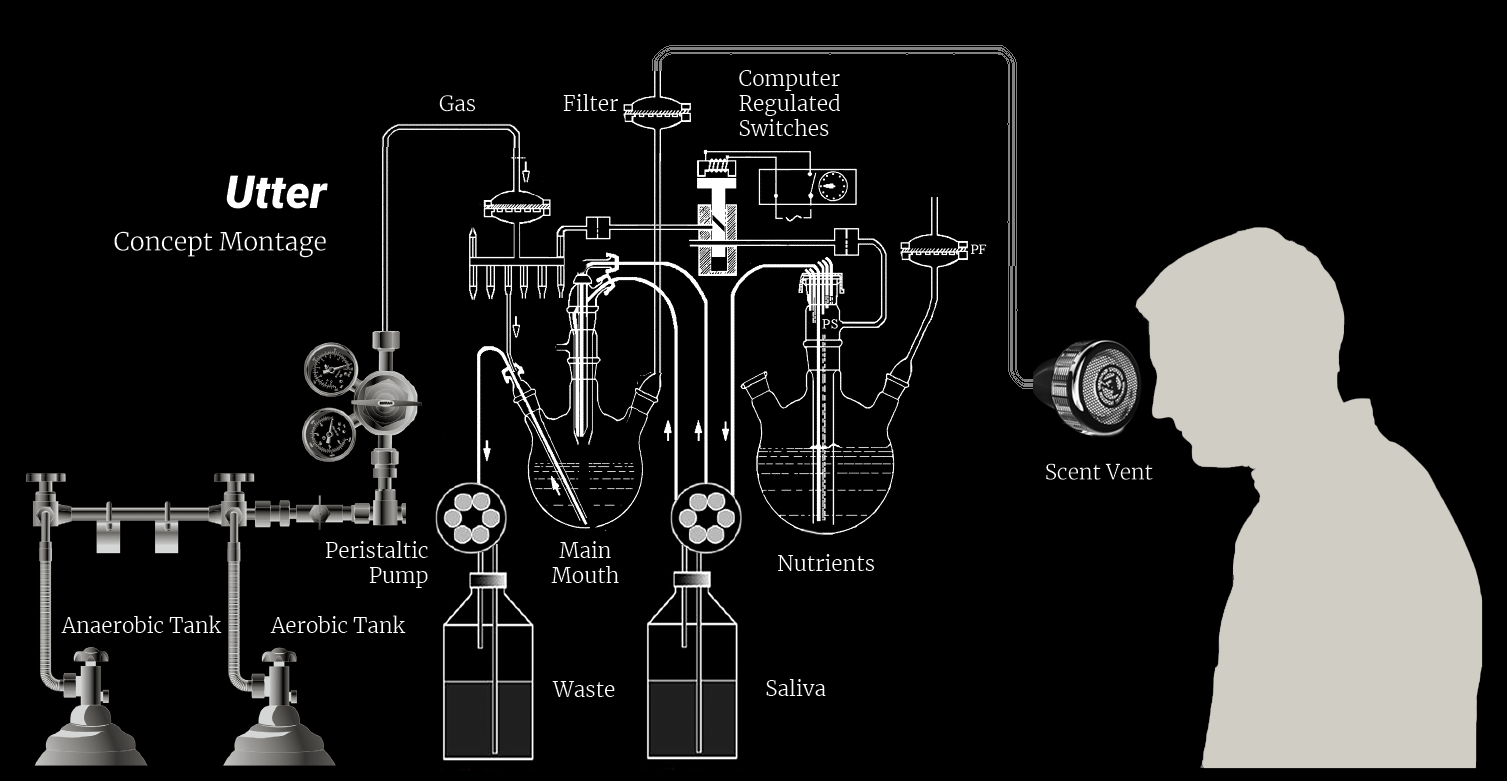

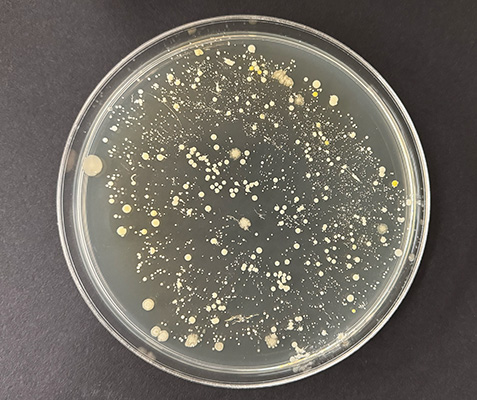

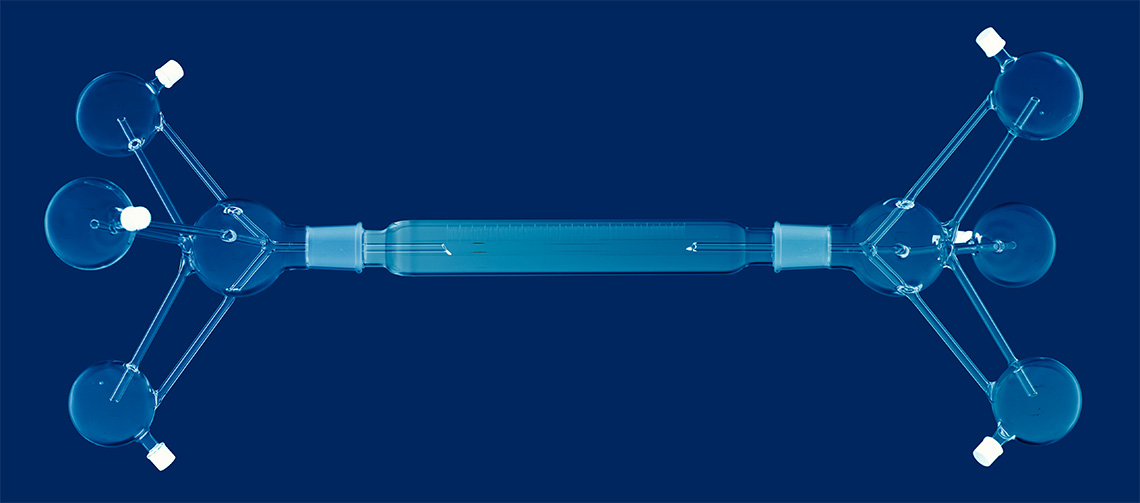

Utter explores the biological processes and social implications of human breath. The goal is a multi-sensory installation, comprised of a series of apparatuses that produce moist, odiferous emissions, simulating human breath, without humans. The apparatuses incubate a myriad of bacterial species native to the human oral cavity in-vitro and release the scented clouds through vents along the apparatuses' perimeter. Air-flow through the system passes through both liquid valve traps and 0.1-micron filters, which allow molecular odors to disseminate, while ensuring viewers are not exposed to microbes. Audiences will experience the work by simply witnessing its fluid mechanical operations or engage olfactorily by approaching vents along the apparatuses’ perimeter which release the scented emissions.

The title references Mikhail Bakhtin, who expanded and liberated the concept of ‘utterance,’ from its usage in early twentieth century linguistics to include non-verbal language and ‘otherness.’ Since Bakhtin, many scholars have embraced the ‘post-semiotic’ turn, including Bruno Latour, who uses the term 'semio-material' to flatten human/non-human and actor/actant hierarchies in their social models. Similarly, Karen Barad uses the term 'material-discursive' to undo the binary opposition between representations and (their) objects, or more simply, between ‘words’ and ‘things.’

Such critiques of the primacy of human language are mirrored by contemporary scientific findings on the human microbiome, the microbes that live on and inside our bodies. It is now recognized that our bodies contain more microbial cells than human cells and that these microbes regulate most of the metabolic and cognitive processes that seemingly ‘make us human.’ Biologist Scott Gilbert concludes that, ‘Animals, therefore, cannot be regarded as individuals by anatomical criteria, but rather as holobionts, integrated organisms composed of both host cells and persistent populations of symbionts.’ The profound ontological implications of such findings are elegantly summed up by Philosopher Lisa Heldke who reflects that ‘… at the (literal) bodily centre of us, we find not some solid, essential core, but the rest of the world. We are literally tubes full of other organisms.’ Reassessing our symbiotic relations with non-human actors profoundly alters classical conceptions of where ‘self' ends and ‘other’ begins.

The smells of the human body are generally considered abject, unwanted and never polite. Much of western culture is designed to minimize body odors—deodorants, toothpastes, mouthwash, breath mints, laundry detergents, soaps, room deodorizers, as well the modern toilet. Historically, odors and myths of their effects, have well served racism, xenophobia, colonialism, and classism—reinforcing stereotypes, enacting boundaries and dehumanizing perceived others. In this context, the Utter project aims to place that which is abject and hidden, back into the realm of ethical reflection and aesthetic contemplation.

The scents of others can arouse such fear as they transgress the very borders of self via a cloud of otherness, literally the material from another’s body. However, audiences experiencing Utter may find these artificially produced, vaguely human scents simultaneously comforting, reminding us of social, physical, and sensual human contact. In the Hawaiian concept of Aloha, Alo means to share while ha is breath, which is also life. The exhaling of the syllable ‘ha’ for the other to breathe in is to share one’s life with another person. ‘Aloha’ can mean a greeting, a welcome, or love, though English translations are inadequate as there is no comparable concept in the West. Could it be possible to experience human scents as a welcoming transformation of the isolated self rather than as a hostile colonizing invasion?

Collaboration and Support

Scientific Advisors and Collaborators

-

Stefan Ruhl, University at Buffalo.

-

Tracy Drier, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

-

Solon Morse, University at Buffalo

Contributors and Consultants

-

Manolo Santos

-

Jessica Jane Julius

-

Rinoi Imada

Support

Pilchuck School of Glass, Seattle, WA.

Salem Community College, Glass Education Center, Salem, NJ.

Coalesce Center for Biological Art, University at Buffalo.

Humanities Institute, University at Buffalo.

Cultivamos Cultura Artist in Residence program, São Luis, Portugal.